What is the future of Mass Transport – Part 2

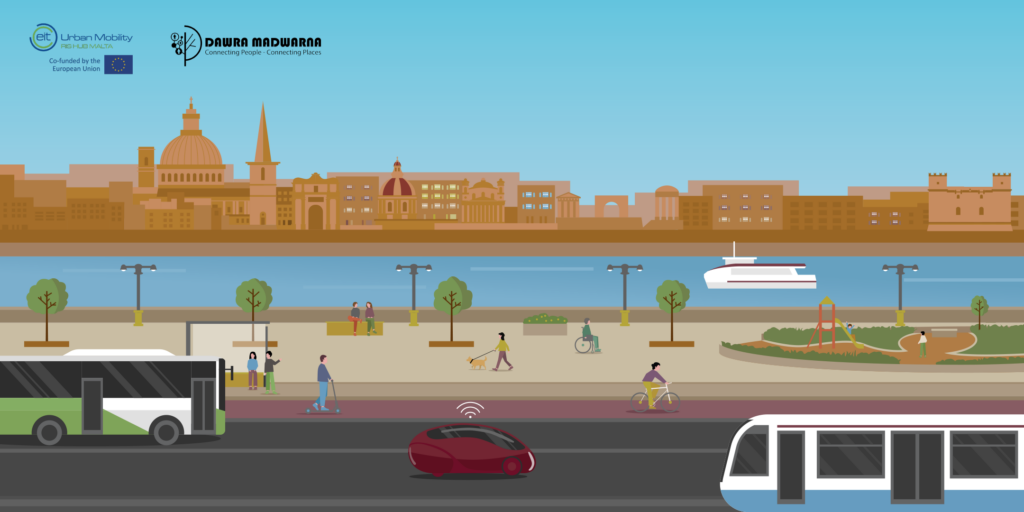

Is the answer a metro, a tram, or the good old bus? On Thursday 15th September, on the eve of European Mobility Week 2022, the EIT Urban Mobility RIS Hub Malta and Dawra Madwarna organised a symposium to discuss the future of mass transport in Malta.

In our first article, we presented the five pitches delivered by selected participants, who shared their ideas for mass transport and improved public transport in Malta. These included a multi-modal network following the former railway, to an on-demand transport system, elevated cycling network and light-rail and bus-rapid transit systems. These inspiring ideas and their potential role in the future of transport in Malta were then discussed with a group of local transport experts.

Visions of a future transport system

Due to Malta’s small size and dense urbanisation, the question of space was raised. Mr. Konrad Pule, General Manager, Malta Public Transport explained that this issue is actually easy to resolve. Many cities are freeing up space by removing on-street car parking. Adapting that example, could create plenty of space by converting car parks into plazas and public spaces for people and moving some of these parking spaces underground. However, as a car-centric culture, even the smallest changes to available parking areas are met with heavy opposition.

While these pitches were inspiring ideas, none of them are particularly new or ground-breaking, as these are solutions that are operational in many other countries. How can Malta come up to speed with the rest of Europe? Dr. Therese Bajada, Lecturer, University of Malta agreed that this is indeed the salient question and posited that it is not rocket science, but that political will is needed to drive change. However, it is not only the policies which are lacking, but that unfortunately public sentiment is very much against these changes; people are unaccepting of measures that would disincentivise private car use. We need to find a balance by making cleaner transport modes attractive to people, but we also need disincentives; today it is still too easy to go everywhere by car and find parking for free. Without a balance between carrots (incentives) and sticks (disincentives) the required modal shift will not happen, Mr. Pule added.

The need for political courage

The shift from private car use to mass transport, only happens in three ways: firstly, as a result of a big shock to the entire country that forces us into change, such as a war or a catastrophic event, secondly, as a result of top-down political direction guided by courageous decisions, and thirdly, public demand, through a bottom-up process. Unfortunately, since the 1930s, every consecutive government has shifted the onus of transport from public to private, removing systems such as the railway and focusing almost solely on building roads. It is very difficult to see change happening, until there is a strong reason for it – Ing. Karl Camilleri, Deputy Director, MCAST (Institute of Business Management and Commerce) posited.

If we make a pogostick the fastest way to move from A to B, people will flock to that mode of transport. We need politicians with vision and guts, who are willing to risk their political career to leave a legacy. Ing. Karl Camilleri thinks that we cannot just tell people that a shift to sustainable modes of transport is “good”, and expect them to follow suit. Rather, you have to force people to make the shift. Libertarian paternalistic policies, through behavioural economics, can be successful, such as in the UK, where such policies were used to turn the tide around, for example to reduce teenage pregnancies and to promote appropriate use of the NHS (National Health Service).

Land use and transport planning need to go hand in hand

Architects and planners need to be the drivers of this change, as they are planning and designing our network and changing the way we design our buildings and the spaces around them will make a big difference, Mr. Pule emphasised. This is indeed what we can see happening abroad, where whole neighbourhoods are planned to be car-free, following the concept of ‘transit-oriented development’ (TOD), making active and public transport the most accessible, convenient and safe way to travel, Dr. Suzanne Maas added.

What can be done in the short-term?

Buses are the backbone of our transport system, and they are the transport means which provides the best accessibility to destinations within urban areas when compared with other forms of public transport. Improving the bus service should be the focus in the short term. Even though improvements have been made, research is showing that timing still needs to be improved. Enforcement would be key to for example remove illegal parking which hinders bus movement. The National Transport Master Plan identifies the need for Public Transport Quality Corridors. There are stretches of bus routes which were identified where buses should be given priority. Currently, we have some stretches of bus lanes however these are not continuous, Dr. Lewis commented. Segregated lanes for cycling and facilitating walking should also be short term focuses. Since most trips locally are short distances, cycling and walking are ideal modes of transport and then buses can be used for longer distances. To make this happen however, introducing disincentives to reduce the convenience of using one’s private car, are essential, Dr. Bajada explained.

Multi-modality is the way forward

In a final round of comments, the panellists summarised their view on the future of (mass) transport in Malta. To proceed we need to improve on what we have. Mass transport is a need, an efficient means to move. A combination of what was discussed could be the way forward. A metro alone is not the solution for Malta. Instead, a multi-modal system, combining different transport modes is required. We need to keep on applying pressure, on transport operators (like Malta Public Transport) and on policy makers. Finally, it is important to consider transport equity: taking a human centric approach by considering the mobility needs of different demographic groups in the community, such as the elderly, people with a disability, young parents with pushchairs, youths and children, so as to create a transport system which works for all.